IT threat evolution Q2 2020

IT threat evolution Q2 2020. PC statistics

IT threat evolution Q2 2020. Mobile statistics

Targeted attacks

PhantomLance: hiding in plain sight

In April, we reported the results of our investigation into a mobile spyware campaign that we call ‘PhantomLance’. The campaign involved a backdoor Trojan that the attackers distributed via dozens of apps in Google Play and elsewhere.

Dr Web first reported the malware in July 2019, but we decided to investigate because the Trojan was more sophisticated than most malware for stealing money or displaying ads. The spyware is able to gather geo-location data, call logs and contacts; and can monitor SMS activity. The malware can also collect information about the device and the apps installed on it.

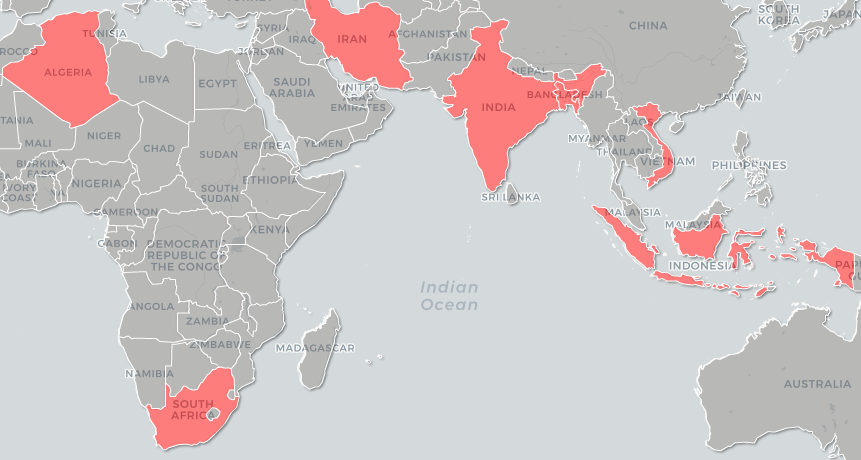

The earliest registered PhantomLance domain we found dates back to December 2015. We found dozens of related samples that had been appearing in the wild since 2016 and one of the latest samples was published in November last year. We informed Google about the malware, and Google removed it soon after. We observed around 300 attacks targeting specific Android devices, mainly in Southeast Asia.

During our investigation, we discovered various overlaps with reported OceanLotus APT campaigns, including code similarities with a previous Android campaign, as well as macOS backdoors, infrastructure overlaps with Windows backdoors and a few cross-platform characteristics.

Naikon’s Aria

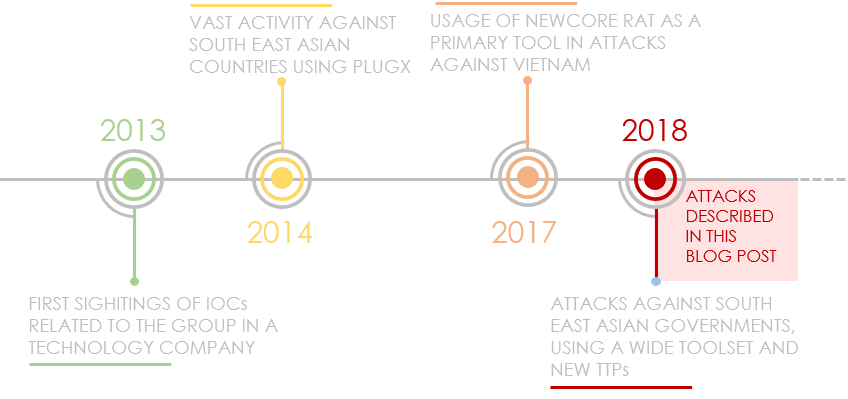

The Naikon APT is a well-established threat actor in the APAC region. Kaspersky first reported and then fully described the group in 2015. Even when the group shut down much of its successful offensive activity, Naikon maintained several splinter campaigns.

Researchers at Check Point recently published their write-up on Naikon resources and activities related to “Aria-Body”, which we detected in 2017 and reported in 2018. To supplement their research findings, we published a summary of our June 2018 report, “Naikon’s New AR Backdoor Deployment to Southeast Asia“, which aligns with the Check Point report.

AR is a set of backdoors with compilation dates between January 2017 and February 2018. Much of this code operates in memory, injected by other loader components without touching disk, making it very difficult to detect. We trace portions of this codebase back to “xsFunction” EXE and DLL modules used in Naikon operations going back to 2012. It’s probably that the new backdoor, and related activity, is an extension of, or a merger with, the group’s “Paradir Operation”. In the past, the group targeted communications and sensitive information from executive and legislative offices, law enforcement, government administrative, military and intelligence organizations within Southeast Asia. In many cases we have seen that these systems also were targeted previously with PlugX and other malware.

The group has evolved since 2015, although it continues to focus on the same targets. We identified at least a half a dozen individual variants from 2017 and 2018.

You can read our report here.

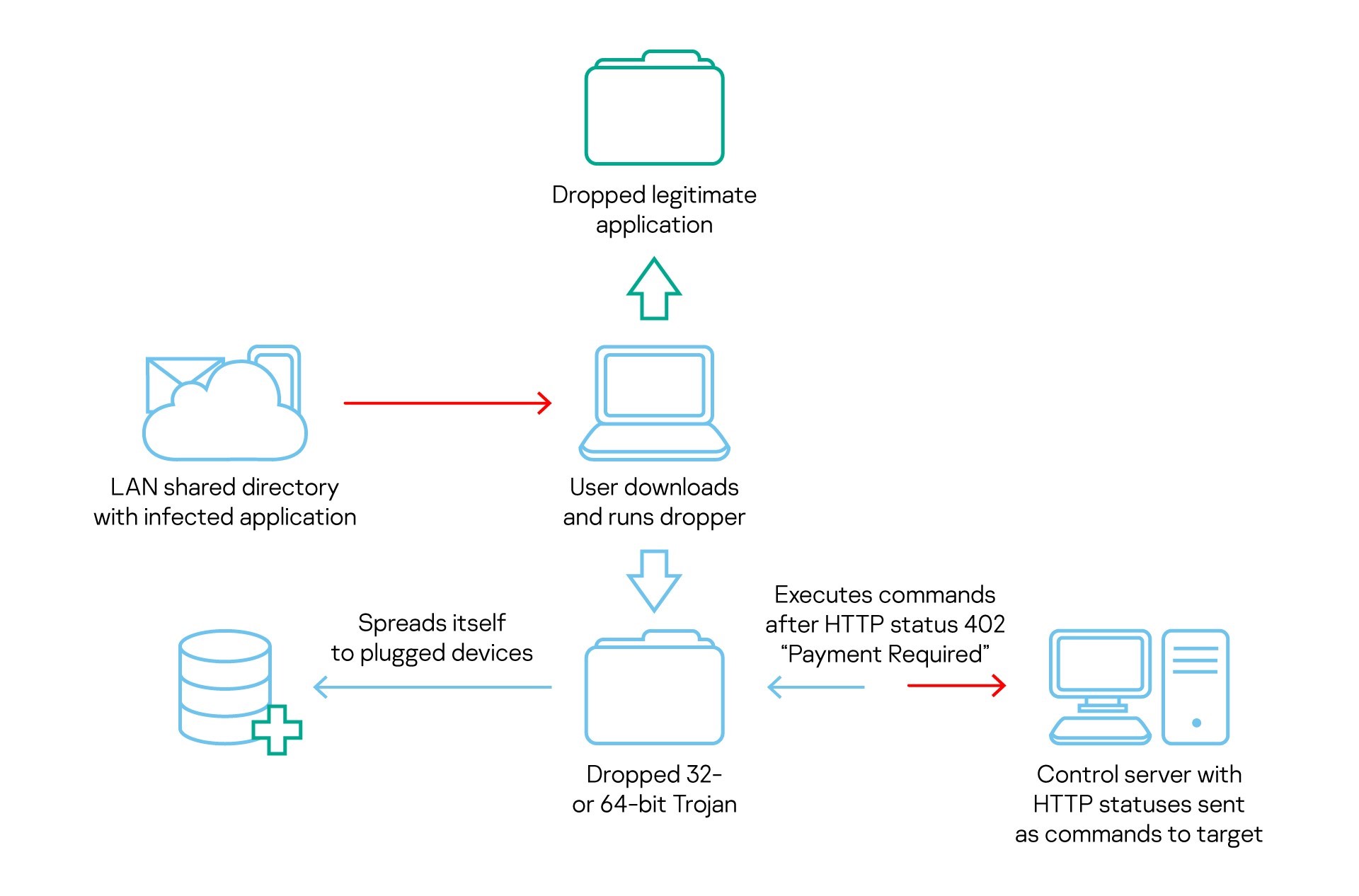

COMpfun authors spoof visa application with HTTP status-based Trojan

Last October, we observed malware that we call Reductor, with strong code similarities to COMpfun, which infected files on the fly to compromise TLS traffic. The attackers behind Reductor have continued to develop their code. More recently, the Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine revealed a new Trojan with strong code similarities to COMpfun.

The new malware, like its predecessor, targeted diplomatic bodies in Europe. To lure their victims, the attackers used spoofed visa applications that contain malware that acts as a first-stage dropper. This in turn downloads the main payload, which logs the target’s location, gathers host- and network-related data, performs keylogging and takes screenshots. The Trojan also monitors USB devices and can infect them in order to spread further, and receives commands from the C2 server in the form of HTTP status codes.

It’s not entirely clear which threat actor is behind COMpfun. However, based mostly on the victims targeted by the malware, we associate it, with medium-to-low confidence, with the Turla APT.

Mind the [air] gap

In June, we published our report on the latest tools and TTPs (Tactics Techniques and Procedures) of Cycldek (aka Goblin Panda, APT 27 and Conimes), a threat actor that has targeted governments in Southeast Asia since 2013.

Most of the attacks we have seen since 2018 start with phishing emails that contain politically themed, booby-trapped RTF documents that exploit known vulnerabilities. Once the target computer has been compromised, the attackers install malware called NewCore RAT. There are two variants. The first, BlueCore, appears to have been deployed against diplomatic and government targets in Vietnam; while the second, RedCore, was first deployed in Vietnam before being found in Laos.

Bot variants download additional tools, including a custom backdoor, a tool for stealing cookies and a tool that steals passwords from Chromium-based browser databases. The most striking of these tools is USBCulprit, which relies on USB media to exfiltrate data from victims’ computers. This may suggest that Cycldek is trying to reach air-gapped networks in compromised environments or relies on a physical presence for the same purpose. The malware is implanted as a side-loaded DLL of legitimate, signed applications.

Looking at big threats using code similarity

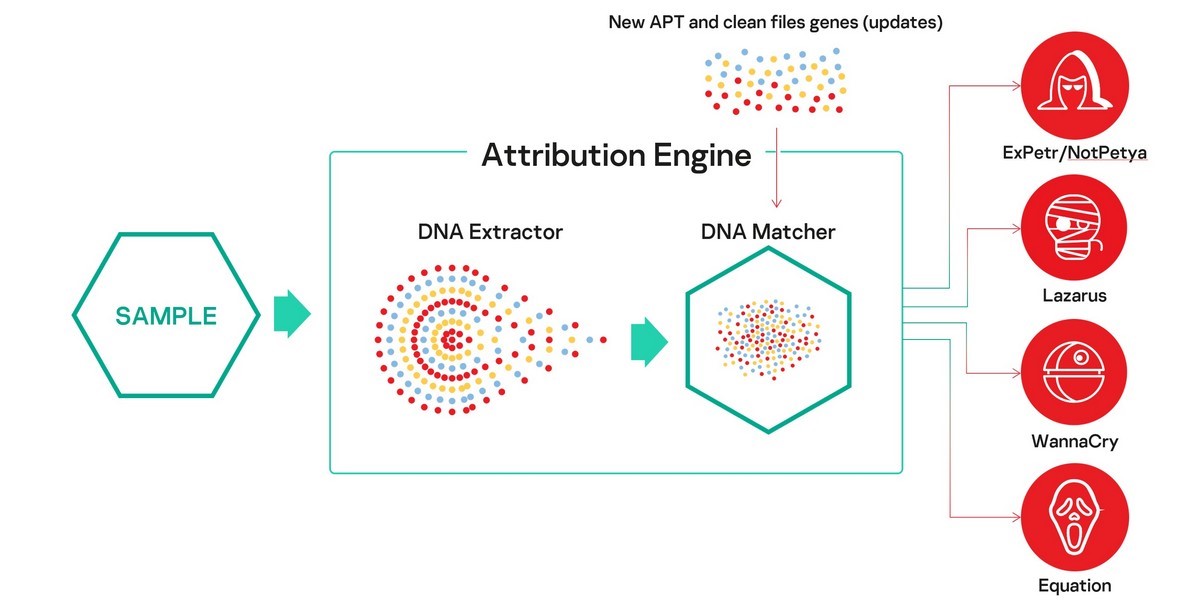

In June, we announced the release of KTAE (Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine). KTAE was initially developed as an internal threat hunting tool by the Global Research and Analysis Team at Kaspersky and was instrumental in our investigations into the LightSpy, TajMahal, Dtrack, ShadowHammer and ShadowPad campaigns.

Here’s how it works in a nutshell. We extract from a suspicious file something that we call ‘genotypes’ – short fragments of code selected using our proprietary algorithm – and compare it with more than 60,000 objects of targeted attacks from our database, using a wide range of characteristics. Based on the code similarities, KTAE calculates a reputational score and highlights the possible origin and author, with a short description and links to both private and public resources, outlining the previous campaigns.

Subscribers to our APT intelligence reports can see a dedicated report on the TTPs used by the identified threat actor, as well as further response steps.

KTAE is designed to be deployed on a customer’s network, with updates provided via USB, to ensure confidentiality. In addition to the threat intelligence available ‘out of the box’, customers can create their own database and fill it with malware samples found by in-house analysts. In this way, KTAE will learn to attribute malware analogous to those in the customer’s database while keeping this information confidential. There’s also an API (application programming interface) to connect the engine to other systems, including a third-party SOC (security operations center).

Code similarity can only provide pointers; and attackers can set false flags that can trick even the most advanced threat hunting tools – the ‘attribution hell’ surrounding Olympic Destroyer provided an object lesson in how this can happen. The purpose of tools such as KTAE is to point experts in the right direction and to test likely scenarios.

You can find out more about the development of KTAE in this post by Costin Raiu, Director of the Global Research and Analysis Team and this product demonstration.

SixLittleMonkeys

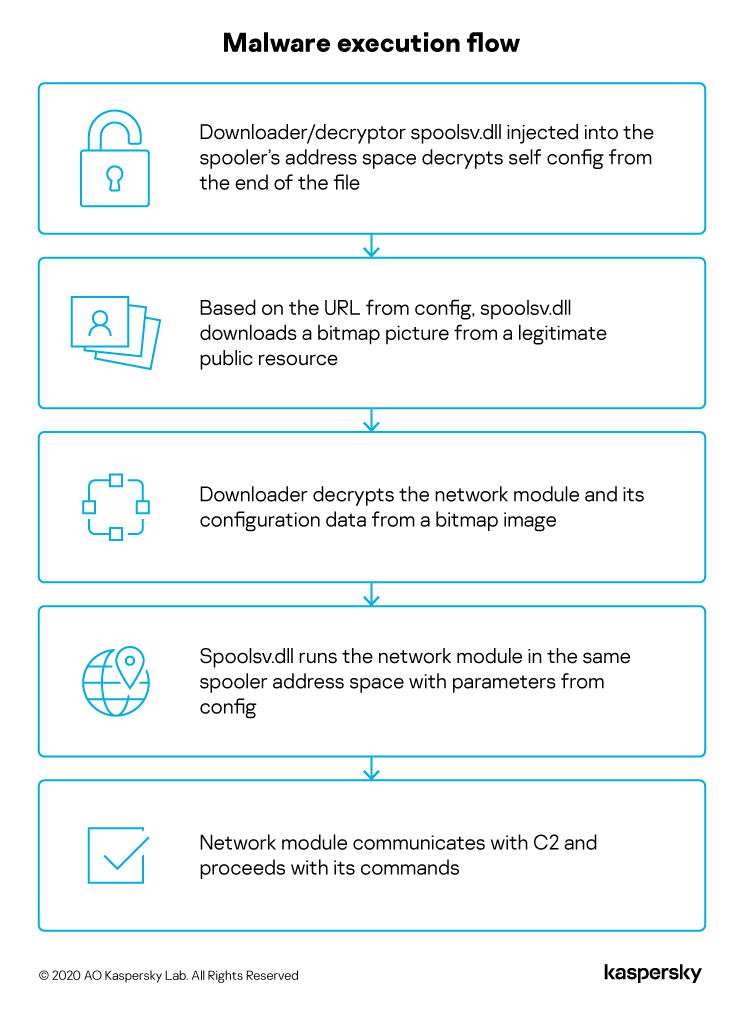

Earlier this year, we observed a Trojan injected into the spooler system process memory of a computer belonging to a diplomatic body. The malware is implemented like an API using an enterprise-grade programming style – something that is quite rare and is mostly used by advanced threat actors. We attribute this campaign to a threat actor called SixLittleMonkeys (aka Microcin) because of the re-use of C2 infrastructure, code similarities and focus on diplomatic targets in Central Asia.

This threat actor uses steganography to deliver malicious modules and configuration data from a legitimate public resource, in this case from the legitimate public image hosting service cloudinary.com:

You can read our full report here.

Other malware

Loncom packer: from backdoors to Cobalt Strike

In March, we reported the distribution of Mokes and Buerak malware under the guise of a security certificate update. Following publication of that report, we conducted a detailed analysis of the malware associated with this campaign. All of the malware uses legitimate NSIS software for packing and loading shellcode, and the Microsoft Crypto API for decrypting the final payload.

Besides Mokes and Buerak, which we mentioned in the previous article, we noticed packed specimens of DarkVNC and Sodin (aka REvil and Sodinokibi). The former is a backdoor used to control an infected machine via the VNC protocol; the latter is a ransomware family. However, the most striking find was the Cobalt Strike utility, which is used both by legal pen-testers and by various APT groups. The command center of the sample that contained Cobalt Strike had previously been seen distributing CactusTorch, a utility for running shellcode present in Cobalt Strike modules, and the same Cobalt Strike packed with a different packer.

xHelper: the Trojan matryoshka

The xHelper Trojan remains as active as ever. The most notable feature of this Trojan is its persistence on an Android device: once it gets onto a phone, it’s able to survive even if it’s deleted or the device is restored to factory settings.

The architecture of the latest version resembles a Russian nesting doll (or ‘matryoshka’). The infection starts by tricking a victim into downloading a fake app – in the case of the version we analyzed, an app that masquerades as a popular cleaner and speed-up utility. Following installation, it is listed as an installed app in the system settings, but otherwise disappears from the victim’s view – there’s no icon and it doesn’t show up in search results. The payload, which is decrypted in the background, fingerprints the victim’s phone and sends the data to a remote server. It then unpacks a dropper-within-a-dropper-within-a-dropper (hence the matryoshka analogy). The malicious files are stored sequentially in the app’s data folder, to which other programs do not have access. This mechanism allows the malware authors to obscure the trail and use malicious modules that are known to security solutions.

The final downloader in the sequence, called Leech, is responsible for installing the Triada Trojan, whose chief feature is a set of exploits for obtaining root privileges on the victim’s device. This allows the Trojan to install malicious files directly in the system partition. Normally this is mounted at system startup and is read-only. However, once the Trojan has obtained root access, it remounts the system partition in write mode and modifies the system such that the user is unable to remove the malicious files, even after a factory reset.

Simply deleting xHelper isn’t enough to clean the device. If you have ‘recovery’ mode set up on the device, you can try to extract the ‘libc.so’ file from the original firmware and replace the infected one with it, before removing all malware from the system partition. However, it’s simpler and more reliable to completely re-flash the phone. If the firmware of the device contains pre-installed malware capable of downloading and installing programs, even re-flashing will be pointless. In that case, it’s worth considering an alternative firmware for the device.

Spike in RDP brute-force attacks

The huge increase in remote working due to the COVID-19 pandemic has had a direct impact on cybersecurity and the threat landscape. Alongside the higher volume of corporate traffic, the use of third-party services for data exchange and employees working on home computers (, IT security teams also have to grapple with the increased use of remote access tools, including the Microsoft RDP (Remote Desktop Protocol).

RDP, used to connect remotely to someone else’s desktop, is used by telecommuters and IT support staff to troubleshoot problems. A successful RDP attack provides a cybercriminal with remote access to the target computer with the same permissions enjoyed by the person whose computer it is.

In the two months prior to our report (i.e. March and April), we observed a huge increase in attempts to brute-force passwords for RDP accounts. The numbers rose from 100,000 to 150,000 per day in January and February to nearly a million per day at the beginning of March.

!function(e,i,n,s)var t=”InfogramEmbeds”,d=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n))var o=e.createElement(“script”);o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src=”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”,d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)(document,0,”infogram-async”);

Growth in the number of attacks by the Bruteforce.Generic.RDP family, February–April 2019 (download)

Since attacks on remote infrastructure will undoubtedly continue, it’s important for anyone using RDP to protect their systems. This includes the following.

- Use strong passwords.

- Make RDP available only through a corporate VPN.

- Use NLA (Network Level Authentication).

- Enable two-factor authentication.

- If you don’t use RDP, disable it and close port 3389.

- Use a reliable security solution.

Even if you use a different remote access protocol, you shouldn’t relax. At the end of last year, Kaspersky experts found 37 vulnerabilities in various clients that connected via the VNC protocol, which, like RDP, is used for remote access.

Gaming during the COVID-19 pandemic

Online gamers face various threats, including malware in pirated copies, mods and cheats, phishing and other scams when buying or exchanging in-game items and dangers associated with buying accounts.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a marked increase in player activity. For one thing, the sales of games have increased:

!function(e,i,n,s)var t=”InfogramEmbeds”,d=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n))var o=e.createElement(“script”);o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src=”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”,d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)(document,0,”infogram-async”);

Growth in game sales in the week of March 16-22. Source: gamesindustry.biz (download)

The amount of time spent playing has also increased:

!function(e,i,n,s)var t=”InfogramEmbeds”,d=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n))var o=e.createElement(“script”);o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src=”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”,d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)(document,0,”infogram-async”);

Growth in game sales in the week of March 16-22. Source: gamesindustry.biz (download)

This hasn’t gone unnoticed by cybercriminals. With the connection of work computers to home networks, and, conversely, the entry of home devices into work networks that are often poorly prepared for this, attacks on players are becoming not only a way to get to an individual user’s wallet but also a way to access the corporate infrastructure. Cybercriminals are actively hunting for vulnerabilities that they can exploit to compromise systems. For example, in the first five months of this year alone, the number of vulnerabilities discovered on Steam exceeded those discovered in any of the previous years.

!function(e,i,n,s)var t=”InfogramEmbeds”,d=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n))var o=e.createElement(“script”);o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src=”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”,d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)(document,0,”infogram-async”);

Vulnerabilities discovered in Steam. Source: cve.mitre.org (download)

Of course, cybercriminals also exploit human vulnerabilities – hence the increase in phishing scams:

!function(e,i,n,s)var t=”InfogramEmbeds”,d=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n))var o=e.createElement(“script”);o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src=”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”,d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)(document,0,”infogram-async”);

An increase in the number of hits on phishing Steam-related topics relative to February 2020. Source: KSN (download)

And the increase in detections on sites with names exploiting the theme of games:

!function(e,i,n,s)var t=”InfogramEmbeds”,d=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n))var o=e.createElement(“script”);o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src=”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”,d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)(document,0,”infogram-async”);

The number of web attacks using game subjects during the period from January to May 2020. Source: KSN (download)

Data from KSN (Kaspersky Security Network) indicate that attackers focus most on Minecraft, followed by CS: GO and Witcher:

!function(e,i,n,s)var t=”InfogramEmbeds”,d=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0];if(window[t]&&window[t].initialized)window[t].process&&window[t].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n))var o=e.createElement(“script”);o.async=1,o.id=n,o.src=”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”,d.parentNode.insertBefore(o,d)(document,0,”infogram-async”);

The number of attacks using the theme of an online game, January-May 2020. Source: KSN (download)

You can read more about this in our full report.

Rovnix bootkit back in business

In mid-April, our threat monitoring systems detected an attempt by cybercriminals to exploit the COVID-19 pandemic to distribute the Rovnix bootkit. The infected file, which has an EXE or RAR extension, is called (in Russian) ‘on the new initiative of the World Bank in connection with the coronavirus pandemic’. The file is a self-extracting archive that contains ‘easymule.exe’ and ‘1211.doc’.

The file includes the Rovnix bootkit.

Rovnix is well-known and the source code published some time ago. And there’s nothing new about cybercriminals exploiting the current pandemic to distribute malware. However, Rovnix has been updated with a UAC (User Account Control) bypass tool, allowing the malware to escalate its privileges without displaying a UAC request. It also uses DLL hijacking to camouflage itself in the system.

This version also delivers a loader that is unusual for this malware. Once the malware is installed, the C2 can send commands to control the infected computer, including recording sound from the microphone and sending the audio file to the cybercriminals, turning off or restarting the computer.

Our analysis of this version makes it clear that even well-known threats like Rovnix can throw up surprises when the source code goes public. Freed from the need to develop their own protection-bypassing tools from scratch, cybercriminals can pay more attention to the capabilities of their own malware and add their own ‘goodies’ to the source code – in this case, UAC bypass.

You can read our full analysis here.

Web skimming with Google Analytics

Web skimming is a common method of stealing the data of online shoppers. Cybercriminals inject malicious code into a target website to harvest the data entered by consumers. They gain access to the compromised site by brute-forcing an administrator account password, exploiting vulnerabilities in the CMS (content management system) or one of its third-party plugins, or by injecting malicious code into an incorrectly coded input form.

One way to prevent this is to try to block the exfiltration of the harvested data using a Content Security Policy (CSP) – a technical header that lists all services with the right to collect information on a particular site or page. If the service used by the cybercriminals is not listed in the header, they will not be able to withdraw any information they harvest.

Some attackers are using Google Analytics to work around this. Most online providers today carefully monitor visitor statistics; and the most convenient tool for doing this is Google Analytics. The service, which allows data collection based on many parameters, is currently used by around 29 million sites. So, there’s a strong likelihood that data transfer to Google Analytics is allowed in the CSP header of an online store. To collect website statistics, all you have to do is configure tracking parameters and add a tracking code to your pages. As far as the service is concerned, if you are able to add this code, you are the legitimate owner of the site. So, the malicious script injected by the attacker can collect user data and then, using their own tracking code, send it through the Google Analytics Measurement Protocol directly to their account.

To prevent these issues, webmasters should do the following:

- Adopt a strict CMS access policy that restricts user rights to a minimum.

- Install CMS components from trusted sources only.

- Create strong passwords for all administrator accounts.

- Apply updates to all software.

- Filter user-entered data and query parameters, to prevent third-party code injection.

- For e-commerce sites, use PCI DSS-compliant payment gateways.

Consumers should use a reliable security solution – one that detects malicious scripts on payment sites.

You can read more about this method here.

The Magnitude Exploit Kit

Exploit kits are not as widespread as they used to be. In the past, they sought to exploit vulnerabilities that had already been patched. However, newer and more secure web browsers with automatic updates simply prevent this. The decline in the use of Adobe Flash Player has also reduced the opportunities for cybercriminals. Adobe Flash Player is a browser plug-in: so even if the browser was up-to-date, there was a possibility that Adobe Flash was still vulnerable to known exploits. The end of life date for Adobe Flash is fast approaching. It is disabled by default in all web browsers and has pretty much been replaced with open standards such as HTML5, WebGL, and WebAssembly.

Nevertheless, exploit kits have not disappeared completely. They have adapted and switched to target people running Internet Explorer that haven’t installed the latest security updates.

Although Edge replaced Internet Explorer as the default web browser with the release of Windows 10, Internet Explorer is still installed for backward compatibility on machines running Windows 10; and has remained the default web browser for Windows 7, 8 and 8.1. The switch to Microsoft Edge development also meant that Internet Explorer would no longer be actively developed and would only receive vulnerability patches without general security improvements. Notwithstanding this, Internet Explorer remains a relatively popular web browser. According to NetMarketShare, as of April 2020, Internet Explorer is used on 5.45% of desktop computers (for comparison, Firefox accounts for 7.25%, Safari 3.94% and Edge 7.76%).

Despite the security of Internet Explorer being five years behind that of its modern counterparts, it supports a number of legacy script engines. CVE-2018-8174 is a vulnerability in a legacy VBScript engine that was originally discovered in the wild as an exploited zero-day. The majority of exploit kits quickly adopted it as their primary exploit. Since its discovery, a few more vulnerabilities for Internet Explorer have been discovered as in-the-wild zero-days – CVE-2018-8653, CVE-2019-1367, CVE-2019-1429 and CVE-2020-0674. All of them exploited another legacy component of Internet Explorer – a JScript engine. It felt like it was just a matter of time until exploit kits adopted these new exploits.

Exploit kits still play a role in today’s threat landscape and continue to evolve. We recently analyzed the evolution of one of the most sophisticated exploit kits out there – the Magnitude Exploit Kit – for a whole year. We discovered that this exploit kit continues to deliver ransomware to Asia Pacific (APAC) countries via malvertising. Study of the exploit kit’s activity over a period of 12 months showed that the Magnitude Exploit Kit is actively maintained and undergoes continuous development. In February this year, the exploit kit switched to an exploit for the most recent vulnerability in Internet Explorer – CVE-2019-1367 – originally discovered as an exploited zero-day in the wild. Magnitude Exploit Kit also uses a previously unknown elevation of privilege exploit for CVE-2018-8641, developed by a prolific exploit writer.

You can read more about our findings here.

While the total volume of attacks performed using exploit kits has decreased, it’s clear that they still exist, remain active, and continue to pose a threat. Magnitude is not the only active exploit kit and we see other exploit kits that are also switching to newer exploits for Internet Explorer. We recommend that people install security updates, migrate to a supported operating system (and make sure you stay up-to-date with Windows 10 builds) and also replace Internet Explorer as their web browser.